Missing the Pynchonian Element

A narrow reflection on "One Battle After Another"

We chose to end our year by attending a screening of One Battle After Another at the Gene Siskel Film Center in Chicago. Both of us found it to be… fine. It is a competent, well-paced action movie with genuine tension throughout. Leonardo DiCaprio was, as always, adequate but miscast (and yes, I mean that he is always the wrong choice for every actual and possible film role). One is left wondering whether Ethan Hawke was busy, because he could actually have played the role of Zoyd Wheeler from Pynchon’s Vineland—indeed, he already played a very similar character in Sterlin Harjo’s excellent limited series The Lowdown, a show that was itself much more authentically Pynchonian than the film Pynchon’s least-loved novel supposedly “inspired.”

My second reflection on this movie—which is genuinely very well done; I surely would have deeply enjoyed watching it on a long flight—is that it is carrying far too much ideological and literary weight for what it is. I anticipate, in fact, that those aspects of the film have likely generated online debates of exceptional annoyingness. Doubtless we have learned a great deal about the dialectical nature of Hollywood productions, about the value of simply portraying revolutionary violence from the point of view of the revolutionaries themselves at all, and we have presumably also learned that Paul Thomas Anderson is a Bad Person with Bad Politics. (To be clear, I have not read any thinkpieces on the film at all, so my apologies if I have mischaracterized the nuanced and informative pieces and rich debate it has inspired.)

I want to take that second point a bit further: PT Anderson doesn’t even have any politics at all. It is clear from this film that he has no interest in or insight into politics beyond a kneejerk boring liberalism. As such, he cannot understand the actual motives of his revolutionaries or sympathize with their aims, much less share Pynchon’s genuine regret at their failures. But even conceding his blindness in advance, what we saw on screen was surprising for its lack of empathetic imagination. Perhaps it was always expecting a bit much for the guy whose career began with “remember when porn was good?” to have any genuine insights into politics, but I somehow did not anticipate that his guiding question would be “remember when activism was porn?”

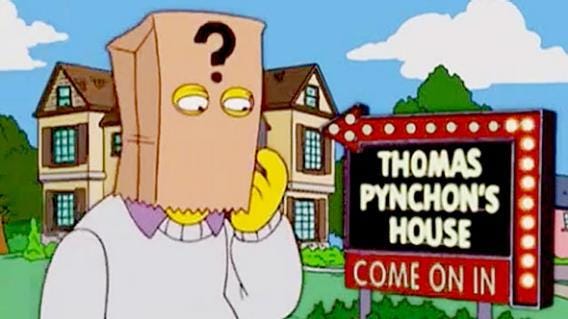

The transgressive sex may be an attempt to capture the spirit of Pynchon, whose novel this film is supposedly adapting in some sense. Pynchon does have a lot of transgressive sex in his novels, often at inappropriate moments (such as right as a bomb is about to go off). Yet it always manages to be somehow poignant and playful, an attempt to capture an uncapturable moment that everyone involved knows to be uncapturable, in fact already lost if it ever existed in the first place…. Pynchon also has a lot of political commentary, a lot of funny names, and a lot of hard-to-follow action setpieces involving characters we barely know. Anderson has dutifully included all of that in his film. But what he’s missing in this adaptation of a Pynchon novel—which he presumably chose because, like Inherent Vice and unlike nearly any of his other works, it passes the laugh test of being filmable at all—is anything like a Pynchonian spirit. And the reason that happened is the same cause that would inspire Anderson to attempt to adapt Pynchon at all despite not “getting” Pynchon: namely, the fact that the director thinks he is much smarter than he is.

Anderson is far from alone in that. Among contemporary directors, one thinks immediately of Christopher Nolan as suffering from a similar syndrome, but there are and have been many others over the years. The French New Wave has a lot to answer for, in convincing big-name directors that they were ipso facto important intellectuals. But at least Nolan has the decency to limit his ambitions to comic books and Father’s Day brick biographies. At least Nolan presumably understands that he does not understand the great postmodern novelist Thomas Pynchon, whose aesthetic project aims to encompass the whole of capitalist modernity and America’s role in it, with a side hustle (represented by his “lesser” novels, including Vineland and Inherent Vice) of mourning the missed opportunity of the counterculture of the 60s and 70s.

In Anderson’s adaptation, it is precisely that mourning that is missing. He portrays the revolution from the inside, and initially it is bound to be seductive to some viewers. But aside from the liberation of the ICE camp—which, by the way, already places us in some kind of weird alternate timeline, in stark contrast to Vineland’s deep integration into America’s real history—we are shown revolutionaries pointlessly blowing up things, simply because they’re adreneline junkies. In the later timeframe, there is a similar dynamic. We see that Benicio del Toro has a functioning network to deal with threats from ICE, which can seamlessly accomodate Leonardo DiCaprio’s needs. But we spend more screen time on Leo’s struggle with the revolutionary phone tree, a gag that might feel Pynchonian but fizzles out into a complaint about the “woke” over-fussiness of the contemporary left—in stark contrast with the real revolutionaries, who call people retards and talk about their “favorite kind of pussy.” (I pause here to note as well Leo’s contempt for “pronouns,” and the fact that the trans character is the one friend who rats the daughter out.)

To the extent there are any politics here, it is an unreflective centrist conviction that the left is bad and annoying even if, for now, the right is more powerful and dangerous. And there is much greater imaginative empathy invested in Sean Penn’s Steven J. Lockjaw and his quest to join the white supremacist Christmas Adventure Club than there is in the incomprehensible McGuffin known as Perfidia Beverly Hills. Here again we are missing the Pynchonian element. Pynchon can understand the genuine seductiveness of authoritarianism—and hence render the romantic relationship between his parallel characters comprehensible—precisely because he is so committed to the left, with all its flaws and failings. And surely Pynchon would never portray the redemption moment of father and daughter as… finally getting smartphones. (My God, my God, how absolutely fucking stupid!)

But there was, in my view, one genuinely Pynchonian moment—the portrayal of the skateboarders who help Leo escape. The way they move, as though they are always skateboarding, is a delight to watch and totally the kind of zany thing Pynchon enjoys. The fact that Leo inexplicably falls off a roof and is captured anyway is also perfect. Why didn’t we get more of that? I suspect it’s because unlike Pynchon, who is fully assured of his status as one of the most erudite and interesting people ever to live, Anderson feels that he has to signal seriousness even in his adaptation of a zany, madcap novel. After all, we’re dealing with major issues, like politics and revolution! But part of what makes Pynchon such a great artist is that he knows that sometimes tragedy can only be approached by way of comedy.

I will say one thing for this film—which I sincerely predict will win the Best Picture Oscar this year, not despite but because of all the flaws I have pointed out—and that is that it makes me want to return to Vineland, and to Peter Coviello’s excellent commentary thereon. I suggest everyone else should do the same. In fact, by the time you get done reading all that, you may not have any time left to watch this competently produced but ultimately forgettable film!

In terms of politics I took the image of an actual functioning Sanctuary City as the literal and metaphorical heart of the movie, intended or not.

Was reading this and the whole time was thinking 'This is a really interesting read of Pynchon that I haven't seen before, where do you suggest I go for more' and then you answered it. Ordering Vineland and the commentary. Good post otherwise as well. I've seen so many different takes on it and my suspicion is the banal centrism you discuss allows people to impose their own politics on it, which leads to a sort of incoherence of opinion in place of consensus.