Spare Capacity

Or, Turns out the seed corn tastes just as good as the regular corn!

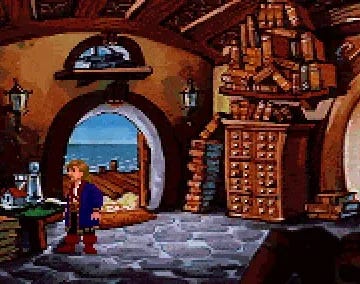

In the classic point-and-click adventure game Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, one of the many gimmicks is a puzzle where you have to check humorously titled books out of a library. One title that always stood out to me was Subtraction: Addition’s Tricky Partner. Growing up, I always felt confident with addition, even if “carrying” was required. But subtraction was another matter entirely—especially the intricacies of “borrowing.” This asymmetry between what was ostensibly two directions of the same operation was, if anything, magnified for multiplication and division. How happy the memory of times tables and multi-digit multiplication problems seem when one is bogged down in long division!

Strangely enough, I have maintained these arcane disciplines well into adulthood. I grew up at a time when keeping a paper check register was a necessary skill, as online banking simply didn’t exist. I am also a control freak—I remember spending hours tracking down the source of the discrepancy when I received a monthly bank statement that was six cents off from my tally. When I entered grad school and thereby became desperately poor, my obsessive tracking proved to be a valuable survival skill, enabling me (against all odds!) to avoid ever overdrawing my bank account even in the most desperate of times. I continue to keep the check register even now, and recently I have made it a point to do all the math by hand — even the dreaded borrowing, even when it would be easy to simply copy the total from the bank website.

I do things like this all the time. I never want to lose skills once I’ve attained them. Often this comes out when I am having my students do group work in class—to prevent myself from bugging them too early on in the process, I’ll put myself a long division problem, or see if I can write out the Greek alphabet. I still maintain a baseline of my piano skills, and I periodically dip back into the many languages I’ve absurdly gained a reading knowledge of. But this new return to the rigors of carrying and borrowing is a bit ridiculous even for me. Why put myself through this, especially since I typically check my bank balance before I’ve had my first cup of coffee?

I believe that I am unconsciously reacting to a typical glib response to concerns over the effects of AI: “People said the same thing about the calculator!” It’s true—they did. And as far as I can tell, they were right. People’s mental math skills are greatly reduced. More importantly, their comfort with and understanding of numbers is obviously less. Without having a grounding in the manual, analog mechanics of connecting numbers with each other, they have less of a sense of what “sounds right.” In many cases, numbers are just something you plug into the calculator without thinking and then accept the result—meaning that one can’t even use a calculator responsibly, because there is no “gut check” that can help correct for an error in entering the initial figures.

Maybe what we lost in the transition to calculators was worth it. Presumably a lot of those mental math skills were meaningless showmanship, and certainly many hand calculations involved meaningless drudgery (often performed by women “calculators” who churned out tables of logarithms, for instance). But it’s important to remember that one reason that the calculator scolds sound so retrospectively foolish is that teachers did not “realistically” accept the “inevitable” but instead prohibited calculator use until baseline math skills had been established—and carefully rationed it even then. If they had not made a concerted effort to protect their pedagogy and had instead allowed students to use calculators at will, it’s likely that we would have had a “lost generation” of students who simply could not do math at all. And the longer that went on, the harder it would be to dig back out of the pit—especially once the kids who grew up with unrestricted calculator use from first grade on grew up to become the math teachers.

And in any case, the skills that were lost in the transition to the calculator era were skills. They were human capacities, distinct ways of using our brains. The fact that they were lost is a loss—maybe not an important one, but a loss nonetheless. In principle, of course, they are still available for anyone who is interested. I’m sure you can watch YouTube videos about how to do cube roots in your head, for example. But no one working alone from YouTube videos is going to get as far as they could have gone when there was a living milieu of people cultivating those skills—developing new algorithms and tricks, maintaining a competitive spirit, and generally making those skills feel valuable rather than like a personal affectation.

For a while, one would see “trad” accounts mourning that Western civilization no longer produces amazing sculptures like Bernini’s Apollo and Dafne (or various other works that, strangely, almost always seemed to feature very realistic nude women). As several respondents pointed out, this was absurd—Bernini was arguably the most accomplished sculptor in world history. Even back in the Renaissance days, they were hardly churning out impossibly intricate masterworks like that. But what made Bernini possible was not simply his own personal aptitude. It was a whole cultural milieu that highly valued the art of sculpture and thus produced a continual push for innovations amid the competition for commissions.

In other words, there is both a diachronic and a synchronic aspect to maintaining skills as “a thing.” If you want a skill to be remembered and practiced in the long term, you must never break the chain: as soon as the sequence of hands-on experienced teachers is broken, rebuilding becomes exceptionally difficult even if written instructions are in principle available. And if you want the skill to be practiced to a high degree of mastery, you need a lot of people to be doing it, because they will keep pushing each other. More interest, more attention, more competition, more prestige—more is more in these matters.

Obviously not every skill needs to be practiced by the mass public. For instance, classical music is pretty culturally marginal at this point, but the level of technical mastery is nonetheless amazing because there is a big enough culture of orchestras and a big enough system of “feeders” to get young people hooked. To a large extent, that has come about because people of Asian descent have sought the cultural capital associated with classical music—a great example of the fact that an important cultural practice need not be maintained only by the culture that originated it in order to survive. But in any case, the result of the robust-enough culture of classical music is that even a middling talent today would likely put the greats of the past to shame, and the very best players today are surely the best players ever to live.

It’s very possible, however, for a skillset to fall below that critical mass. Something like that seems to have happened in the study of classical languages, for example. A century ago, most college-educated people would have studied Greek and/or Latin at least to the point of being able to stumble through a text on their own. Even after that heyday, one hears tales like that of Peter Brown, who went out rowing and read Augustine in Latin without a lectionary, for leisure. There are still people like that—I once participated in a summer seminar on Plato and it was clear that at least one colleague my age could read Greek philosophy very fluently and was extremely well-versed in the intricacies of Plotinus vs. Iamblichus—but they are rare. And it’s not just because of the decline in prestige of classical studies, but also likely because of the availability of online tools like Perseus. I’m grateful for the existence of such tools, as I am for things like Qur’an Gateway or interlinear translations of the Bible. All of those tools give a wider range of people access to ancient texts—but that very ease of access can sap one’s resolve to develop the kind of linguistic mastery that’s necessary to really get a “feel” for the texts in a serious way.

And maybe that’s no big deal! Maybe looking up a Greek word in Plato here and there to prove a point is enough for most of us. And maybe the surprisingly robust demand for fresh translations of Homer—which come out at an astonishing clip year after year—is holding open the space where people can devote their full attention to ancient Greek. But it’s very possible to imagine “breaking the chain” within the next generation, especially as even undergraduate classics majors are no longer required to have serious familiarity with the languages.

Again, maybe we won’t miss Greek and Latin when they’re gone, just as we won’t miss the ability to fluently use a slide rule or do complex mental arithmetic. Yet I’m haunted by a quote from Simone de Beauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity: “One can do without Latin, without cathedrals, and without history. Yes, but there are many other things that one can live without; the tendency of man is not to reduce himself but to increase his power.” We are living amid unprecedented abundance, and the example of classical music shows that it is possible to keep heritage skills and artforms vibrant. We could break the chain—stop doing live orchestral music and stop putting instruments into kids’ hands in grade school to see if they’re interested. In a way, nothing would be lost, because we have all the recordings, and you can do a YouTube instructional video if you want to figure out how to play the violin. But surely it would matter that no one could actually do classical music anymore. We as a human species would be able to do less stuff. It would be a loss. And enough people see that, at least for the time being, to guarantee that sufficient resources are devoted to those weird pursuits that people can still attain a very high level of mastery and the chain will not be broken in the foreseeable future.

That does not seem to be the case with skills like reading, however. Arne Duncan’s Education Department apparently decided that building up the skills necessary to read, and therefore write, extended narrative or argumentative texts was no longer necessary. The advent of smartphones and their uncontrolled release among young people destroyed the attention span of a generation and more or less guaranteed that almost no students would just pick up those skills on their own. Now the availability of AI “summaries” (apparently a much-demanded thing, though I don’t recall this pent-up demand for “summaries” prior to the trillion-dollar boondoggle of LLMs) seems to be on the verge of delivering a death blow. The experiment in mass literacy is in danger of being wound down in the space of a single decade.

Maybe it’s no big deal! After all, most people don’t like reading and don’t do it voluntarily as adults. Most jobs don’t require in-depth reading, and the availability of good-enough LLM tools promises to reduce the number of those that do. In that context, do we really “need” to spend valuable pedagogical time and energy attempting to give everyone the baseline skills to follow extended narratives and arguments and potentially to develop their own? Arguably we don’t. We can do without that, as a society, or at least with much less of that—because presumably we need at least some core of people who can still read and write and understand on their own, if only to check that the AI is properly calibrated.

But the smaller the circle is, the less the arts of reading and writing will be pushed forward, and the greater the chance of eventually breaking the chain. And in the meantime, millions of people who would have had the chance to develop the difficult but rewarding skills that have been foundational for—indeed, all but synonymous with—intellectual achievement for millenia… won’t. Many, perhaps even most, would have chosen not to develop or even use those skills in any serious way, but at least they would have been free to make that sad choice. In the scenario that seems to be approaching, they’re not even being given the chance. And this is happening without anyone deliberating or voting or even directly deciding that we as a society don’t want mass literacy.

It drives me insane with grief. It ruins every day of my life at least a little, simply to know this is going on—much less to face its consequences in the college classroom. And the fact that this can be allowed to happen, that it can take such deep root even before coming to the attention of politicians and journalists as a problem, shows that we may have already broken the chain on even more fundamental skills of democratic deliberation and collective responsibility—or perhaps never actually attained them in the first place.

I remember reading Plato’s Sophist and some other dialogues in Greek for a class in 2007, and how it opened a new vein into understanding him—the structure of the sentences, the wordplay, all of it impossible to capture 100% in translation. Even then I was unprepared going in for how differently the text would feel in Greek than English; now almost no one will learn that Plato is actually “like that.” Trying to render his work, or that of another author like Aristophanes, is a huge challenge but one that’s been sustained for centuries. So yeah it’s grim to think we could someday say “well, we’re done with Greek translations, here’s the optimized summary-translation you asked for.” It can never really be “finished” because there is no optimization or perfect rendition, there are always tradeoffs…time to stockpile Loeb editions heh